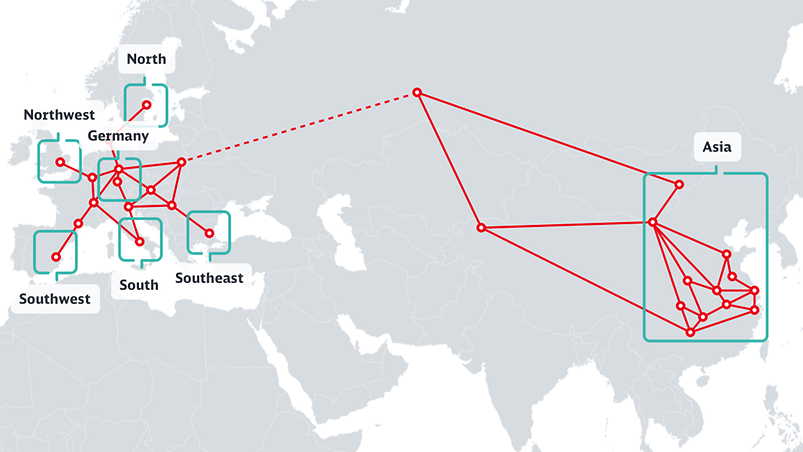

From Sweden to Spain to China, we have good connections

With tailored, customer-centric services, we ensure efficient and reliable transport in Europe and beyond.

How our international solutions help you

- 4,200 customer sidings for fast, reliable, frequent and flexible connections

- Combines the benefits of road and rail

- The strong network in Europe and all the way to Asia

- The largest fleet

- Different commodity groups in each wagon possible

- Environmentally friendly transport with at least 85 percent emission savings

- Additional services: including Track & Trace, collection service, labelling and storage

- Combination of different modes of transport, whether road transport, rail, intermodal, Eurasia or short sea

- Largest logistics network on rail and road

Our shuttle service

Alsace-shuttle - Connection between Eastern France and Offenburg

The shuttle service in a nutshell: Connects numerous chemicals clusters in eastern France with DB Cargo's single wagon network in Offenburg in Germany's Baden region.

The benefits for you:

- 5 departures per week (Mon-Fri)

- Specially tailored to the needs of customers in the chemicals and steel sectors

Your contact:

Control Tower Duisburg SWT France+ 49 203 454 1660DBCargo-CT-SWT-France@deutschebahn.com

Antwerp-shuttle - Rail transport connecting Antwerp and the Ruhr and Rhine/Neckar regions

The shuttle service in a nutshell: Conventional and intermodal rail transport connecting the Belgian industrial region of Antwerp and the surrounding ports to the Ruhr and Rhine/Neckar regions.

The benefits for you:

- Up to 11 departures a week from Antwerp

- Transport times under 24 hours

- Conventional wagonload and intermodal services

- Terminal-to-terminal and siding-to-siding services

- Links up terminals and connecting services in Antwerp, the Rhine/Ruhr region and the Rhine/Neckar region.

Your contact:

Jo Goyvaerts +32 3 545-9890 jo.goyvaerts@deutschebahn.com

Burghausen-shuttle - Connection from Southern to Northern Germany

The shuttle service in a nutshell: We connect the Bavarian chemical triangle to the seaports in Hamburg, Bremerhaven and Wilhelmshaven via the Maschen hub.

The benefits for you:

- Multiple weekly departures

- 8 departures per week/direction

- Open intermodal shuttle train connection

- Cost-effective, reliable and environmentally friendly

Your contact:

Thomas PiegerHead of Sales and Operations Center Chemicals+49 6131 1573160thomas.pieger@deutschebahn.com

Kecskemét-shuttle – Connection between Stuttgart and Hungary

The shuttle service in a nutshell: Fast and reliable shuttle connection between Kecskemét and Kornwestheim with the possibility of seamless international and national onward transport to destinations such as Bremen, Hamburg and Stuttgart

The benefits for you:

- Secure transport of intermodal loading units and conventional rail wagons (e.g., sliding wall wagons)

- 5 departures per week/direction

- Economic and environmentally friendly transport

Your contact:

Rebekka LehmannSenior Account Manager DB Cargo LogisticsTel.: +49 1523 2110913rebekka.lehmann@deutschebahn.com

Mediterranean-shuttle - Fast service between Germany and Spain

The shuttle service in a nutshell: Fast service between Germany and Spain, tailored to the requirements of the automobile industry. Especially high frequency and capacity utilisation achieved by combining transports.

The benefits for you:

- Several departures per week

- Fleet and equipment tailored to the sector

- Flexible freight volumes

- Punctual journeys

- High degree of security through end-to-end consignment tracking

- Central processing by our customer service centre in Duisburg

Your contact:

Laura DeckerSales and Solution Designlaura.decker@deutschebahn.com

Power Railer - The leading block train system to South East Europe

The shuttle service in a nutshell: The leading block train system to South East Europe.

The benefits for you:

- Collection and delivery by rail wagon (if there is a siding) or truck (handling via railports)

- Significant reduction of transport costs, especially for heavy goods or voluminous shipments

- High departure frequencies to SOE

- Pre-carriage or post-carriage by rail or truck possible, e.g., in Turkey, Greece, Macedonia, etc.

Your contact:

Igor HribarHead of Sales FLS - Region Southeast Europe+43 699 1156 1044igor.hribar@deutschebahn.com

Romania-shuttle - Connection between Schwandorf and Romania

One scheduled departure from Schwandorf every second Wednesday (additional departures possible).

Distribution to the satellites from Craiova in Romania to Robanesti, Raureni, Calarasi and Calinesti (further connections possible).

Suitable goods: metal products, wood, paper, chemicals and agricultural products.

Your contact:

Alexander Gelpke & Matthias Witteckalexander.gelpke@deutschebahn.com & matthias.witteck@deutschebahn.com

Turkey-shuttle - Connection between Schwandorf and Turkey

One scheduled departure every Friday from Schwandorf.

Wagons available for reloading for transport to Turkey (Ha and Hb wagons).

Your contact:

Alexander Gelpke & Matthias Witteckalexander.gelpke@deutschebahn.com & matthias.witteck@deutschebahn.com

Get in touch with our experts.

DB Cargo AG